“Didn’t Leave Nobody But the Baby” feels like a spell sung in three voices—sweet as a cradle song, yet edged with danger, as if innocence is being used as bait.

When Emmylou Harris joined Alison Krauss and Gillian Welch on “Didn’t Leave Nobody But the Baby,” the result wasn’t just a lovely harmony performance—it was one of those rare recordings that seems to hover in the air, half-lullaby and half-warning. The track was released as part of the O Brother, Where Art Thou? (Soundtrack) on December 5, 2000, produced by T-Bone Burnett, and it quickly became inseparable from the film’s most unforgettable sequence: the “siren” scene, where beauty and peril arrive wearing the same dress.

In strict chart terms, the song itself was not a standalone commercial single with a major chart “debut position.” Its impact rode on the tidal wave of the soundtrack, which—against every industry expectation for a roots-heavy compilation—reached No. 1 on the Billboard 200 and stayed there for 15 weeks, turning old-time music into a mainstream event in the early 2000s. That same cultural surge carried the album all the way to Grammy Album of the Year at the 44th Annual Grammy Awards.

Awards-wise, “Didn’t Leave Nobody But the Baby” gained prestigious recognition in its own right: it was nominated for Best Country Collaboration with Vocals at the 44th Grammys—a fitting category for three singers whose blend feels less like stacking parts and more like weaving a single piece of cloth. That year, the category was won by The Soggy Bottom Boys (the film’s fictional band persona) for another soundtrack centerpiece, which only underscores how completely O Brother dominated the roots conversation at that moment.

But the real story of this song is older than 2000—older than any award, older than the film’s sepia glow. The piece is an elaboration of an old Mississippi tune tied to field-collection work associated with folklorist Alan Lomax, and for the O Brother version, Welch and Burnett expanded the lyric—a modern touch applied with a traditional hand. That heritage matters, because it explains the song’s uncanny emotional chemistry: it doesn’t sound “written for a movie.” It sounds like it was already in the ground, waiting—something passed along through mouths rather than through paper.

And then comes the central paradox: it’s a lullaby that doesn’t feel entirely safe. The melody rocks gently, yes, but there’s a slyness in the phrasing, a hush that suggests intention. In the film’s context, those intentions are unmistakable: the “baby” becomes a decoy word, the kind you use to make danger look domestic. Harris, Krauss, and Welch sing with angelic poise, yet the combined effect is magnetic, even slightly unnerving—the way a perfectly still pond can look right before you realize it’s deeper than it appears.

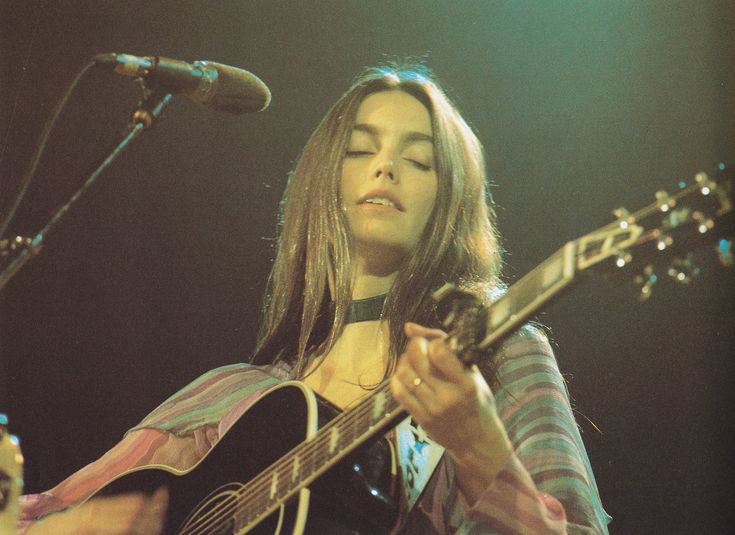

What makes Emmylou Harris so essential here is her particular emotional authority. By 2000, she had already spent decades proving she could honor tradition without embalming it. In this performance, she doesn’t overpower; she steadies the blend. Alison Krauss brings that clear, crystalline purity—an almost weightless precision—while Gillian Welch contributes the shadowed earthiness that keeps the lullaby from floating away into prettiness. Together, the three voices create a “chorus of sirens” that never raises its volume, because it doesn’t need to. The seduction is in the calm.

In the end, “Didn’t Leave Nobody But the Baby” endures because it understands something timeless: sweetness can be a mask, and the most haunting songs rarely announce their darkness. They smile as they sing. They soothe as they warn. And once you’ve heard those three voices circling one another—Emmylou Harris, Alison Krauss, Gillian Welch—you don’t just remember the scene. You remember the feeling of being gently pulled toward something you probably should resist.