“Save the Last Dance for Me” is a love song built on trust: let the world have its moment with you—just promise you’ll come home to me when the music ends.

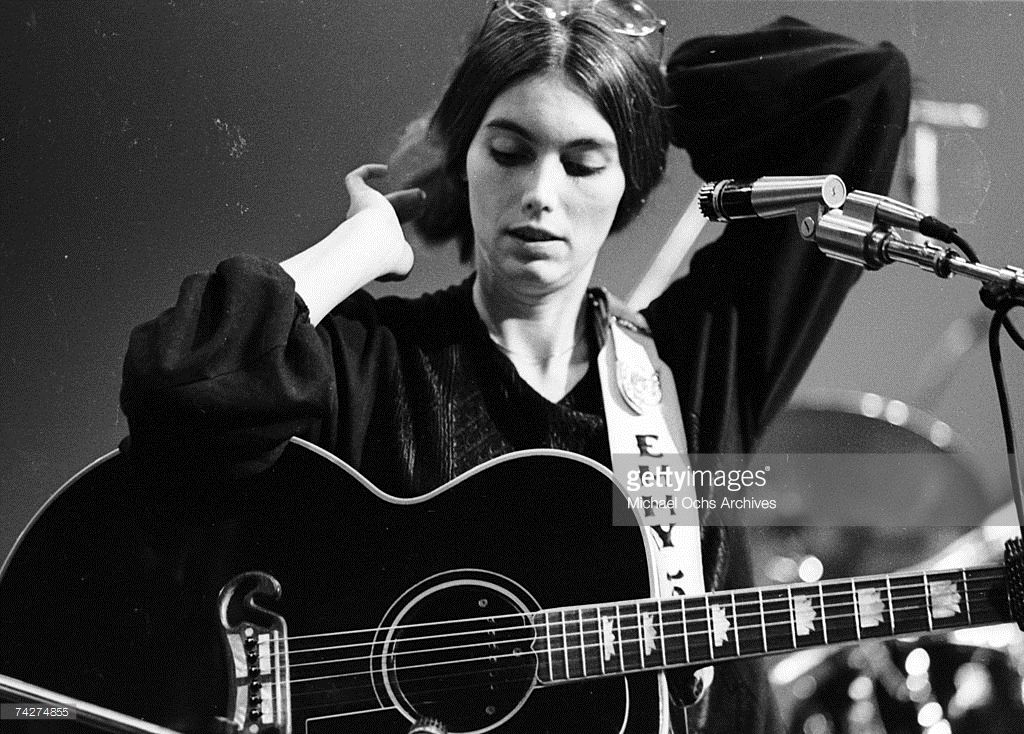

When Emmylou Harris recorded “Save the Last Dance for Me” for her album Blue Kentucky Girl (released April 13, 1979, produced by Brian Ahern), she didn’t treat it as a nostalgia exercise. She treated it like a quiet confession—one that has learned, the hard way, that devotion is not proven in public, but in what happens after the party lights dim. The result was more than an album highlight: her single release became a major country hit, reaching No. 4 on Billboard’s Hot Country Singles and No. 20 on Canada’s RPM Country chart.

That chart peak matters because it captures the surprising power of what she did: she took a 1960 pop-soul classic and made it feel country, not by changing its heart, but by revealing its ache. The song was originally written by Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman and first recorded by The Drifters in 1960 with Ben E. King on lead vocal—then it went all the way to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 (and also topped the U.S. R&B chart). In other hands it can feel like an irresistible dance-floor plea, sweet enough to grin through. In Emmylou’s hands, it becomes something more adult: a vow spoken softly because it’s too important to waste on theatrics.

The story behind the song is one of pop music’s most bittersweet truths. The Financial Times’ “Life of a Song” feature retells the poignant irony at its center: Doc Pomus, who had polio and couldn’t dance, wrote from the perspective of someone watching his bride dance with others—urging her to enjoy the night, but to “save the last dance” for him. That isn’t jealousy; it’s tenderness sharpened by circumstance. It’s the kind of love that says, I won’t cage you. It’s also the kind of love that quietly admits, I still need to know I’m the one you return to.

On Blue Kentucky Girl, Emmylou places “Save the Last Dance for Me” as track 5, right in the middle of an album that leans deliberately toward tradition—an answer to critics who said her records weren’t “country” enough. The track listing itself reads like a map of her taste and her values: songs from Willie Nelson, Gram Parsons, Jean Ritchie—material chosen not for trend, but for truth. In that company, “Save the Last Dance for Me” doesn’t feel like a pop intruder. It feels like a standard that always belonged to the emotional core of country music: fidelity as a private promise.

Listen to the lyric through Emmylou’s lens and the meaning deepens. The singer isn’t demanding ownership—she’s asking for loyalty. “Dance with whoever you want,” the song says in spirit, “but don’t let the night confuse you about where your real tenderness lives.” That is a very grown-up kind of romance: not the fantasy that temptation disappears, but the hope that commitment can still stand upright in the middle of temptation—calm, unshaken, quietly proud.

And then there’s Emmylou herself—the way her voice carries both light and shadow at the same time. She doesn’t oversell the plea. She trusts it. That’s the paradox that made her such a powerful interpreter: she can sound airy and crystalline, yet the emotion underneath is heavy enough to anchor you. On “Save the Last Dance for Me,” she sings like someone who already knows the world is full of strangers willing to twirl you around for a verse—but only one person is waiting for the final chorus.

Maybe that’s why the song keeps returning across decades. We change, the times change, the dance floors change—but the human hope stays stubbornly the same: Go ahead, live your life… just don’t forget me when it matters. In 1979, Emmylou Harris gave that hope a new shape—country-shaped, clear-eyed, and tender enough to last—until the last dance arrives, and the promise is finally kept.