A Lonesome Cry from Behind Bars That Echoes Through the American Soul

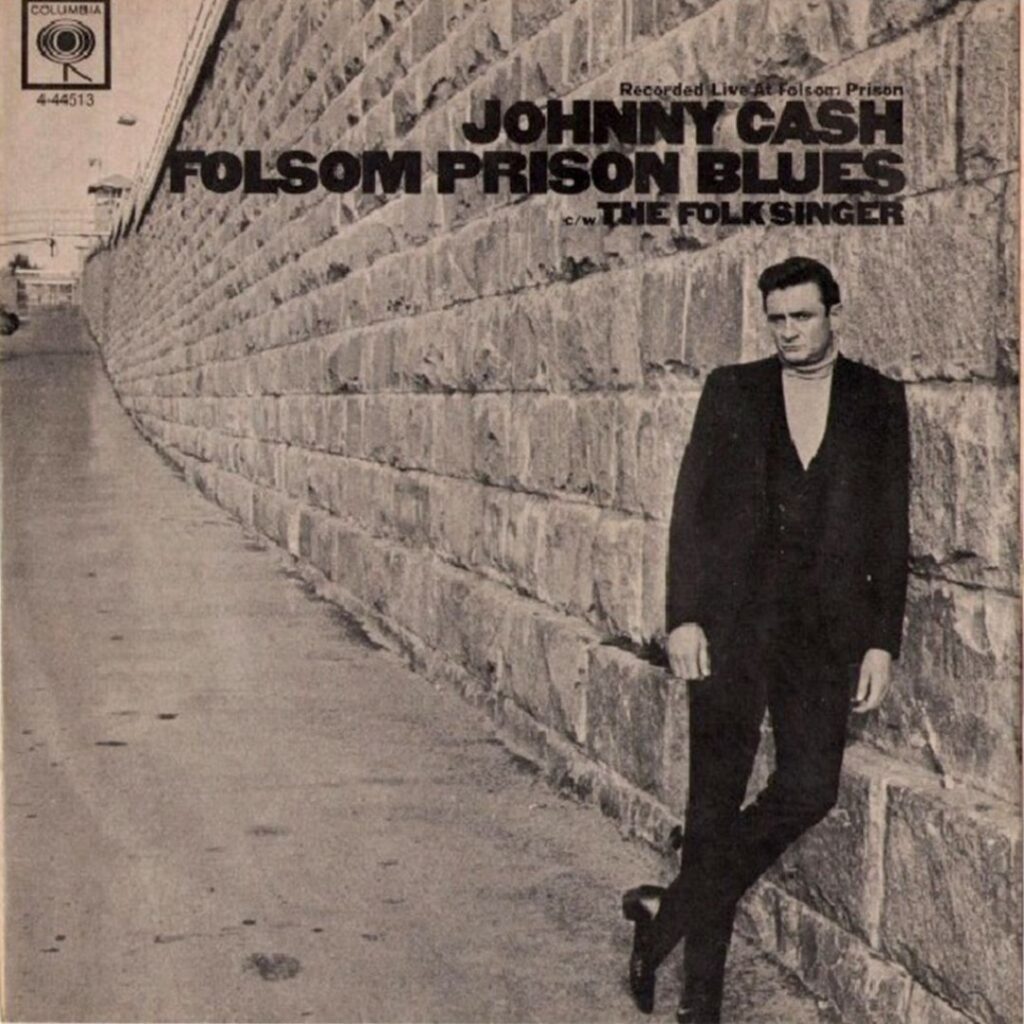

When Johnny Cash released “Folsom Prison Blues” in 1955 as part of his debut album With His Hot and Blue Guitar, few could have predicted that this raw, unvarnished ballad would become one of the defining songs of American country music. Though it peaked modestly at number four on the Billboard Country & Western Best Sellers chart, its legacy has long since outgrown any numerical ranking. Over time, “Folsom Prison Blues” evolved from a stark portrait of regret into a cultural cornerstone, forever entwined with Cash’s mythic outlaw image—an image he would later immortalize during his electrifying 1968 live performance at Folsom State Prison.

The origins of “Folsom Prison Blues” trace back to Cash’s early fascination with the American West and the rough-hewn balladry of sorrowful men trapped by fate and folly. Inspired in part by Gordon Jenkins’ 1953 track “Crescent City Blues,” Cash reimagined the mournful template through his own moral lens, fashioning a character whose brutal honesty struck a nerve with postwar America. The infamous line—“I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die”—is more than a lyric; it’s an existential confession that lays bare the darkness within, one that doesn’t plead for forgiveness so much as it demands to be heard.

Musically, “Folsom Prison Blues” is as lean and deliberate as a prison corridor at midnight. Cash’s voice is resolute, unwavering—delivering each line like a man resigned to the weight of his own deeds. The song’s iconic “boom-chicka-boom” rhythm, pioneered by his backing band, The Tennessee Two, lends a steady, almost train-like momentum, echoing both the physical movement of the locomotive referenced in the lyrics and the psychological yearning for escape it symbolizes. That lonesome whistle becomes more than background noise—it’s a siren call to freedom, taunting the imprisoned narrator with every passing mile.

What makes “Folsom Prison Blues” endure is its unflinching duality: it captures both consequence and longing, guilt and humanity. It does not romanticize crime or absolve its narrator; instead, it invites us into a place where punishment is eternal but memory and regret are even harsher wardens. In this way, Cash wasn’t just singing about prison—he was illuminating the invisible walls we all build around ourselves through choices we wish we hadn’t made.

Decades later, “Folsom Prison Blues” remains one of Johnny Cash’s most profound artistic statements—not merely because of its prison setting or outlaw persona, but because it confronts listeners with a timeless question: can redemption be found when you’ve locked yourself away from grace? For many who first heard it spinning on dusty vinyl or echoing through prison yards, the answer came not in absolution—but in the shared burden of truth.